Complement C3 Triggers Malignant Progression of Mesenchymal Subtype Glioma by ShengfuShen,Xun Jin* in Open Access Journal of Biogeneric Science and Research

Abstract

Patient safety, quality, and efficiency are global issues, therefore hospitals must be able to apply clinical pathways through clinical pathways as the main facilities and infrastructure, especially in services for increasingly acute drug addicts. This study aims to analyze the implementation of clinical pathways for drug rehabilitation program outcomes on 1) clinical quality, 2) cost, 3) readmission, 4) satisfaction, and 5) LOS, at RSJD Atma Husada Mahakam. This type of research uses cross-sectional with observational analytic, data collection through distributing questionnaires to 111 respondents, observation and literature study. The results showed that the clinical quality before and after the implementation of the clinical pathway had a significant effect, but the cost of treatment did not show any significance. There is a positive relationship between readmission and the implementation of clinical pathways, as well as addict satisfaction in the LOS rehabilitation room has a significant effect on treatment time and clinical pathways. A recommendation that the 5 (five) variables mentioned above, apart from being cost-effective, can improve the quality of drug rehabilitation services at RSJD Atma Husada Mahakam Samarinda, so it needs to be maintained

Keywords: Outcome; Quality Clinic; Readmission; Cost, Satisfaction; Length of Stay

Introduction

Glioma is the most common primary intracranial tumor. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system is divided into Ⅰ-Ⅳ glioma grade [1]. Among them, the most invasive tumor is glioblastoma (GBM), WHO IV grade, which is characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation, diffuse infiltration, tendency to necrosis, strong angiogenesis, and chemoradiotherapy resistance [2,3]. At the transcriptome level, GBM can be divided into three subtypes: proneural (PN) ,classical (CL) and mesenchymal (MES)[4,5]. However, different subtypes of glioma prefer different tumor microenvironments [6]. Among them, MES subtype glioma is highly enriched in necrosis area with hypoxia and strong inflammation [7,8]. Clinically, MES subtype glioma is very difficult to treat, due to its strong chemoradiotherapy resistance [9,10]. However, the relationship between chemoradiotherapy resistance and inflammation is unclear. In fact, most inflammation is triggered by a strong immune response [11,12]. As an important part of the innate immune response, complement also plays an important role [13].

Complement has been described as an important factor in the pathogenesis of many central nervous system diseases including infectious, autoimmune and degenerative disorders [14-16]. Complement overexpression is associated with acute brain injury and chronic neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease [17, 18] and Huntington’s disease [19]. Furthermore, C3 serves as a stage-biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [20]. Recently, complement C3 was found to be upregulated in all models of meningeal metastasis, and proved to be essential for the growth of cancer in meningea [21]. However, The role of complement C3 in glioma is not certain. In this study, we firstly found that complement C3 is associated with poor prognosis in glioma patients. Then, C3 may regulate malignant progression of glioma through NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways. Finally,C3 is highly expressed in MES subtype glioma and enhances its chemoradiotherapy resistance.

Material and Methods

Data Mining from Public Databases

First, we searched ONCOMINE databases (https://www.oncomine.org/resource/main.html) to observe the expression of C3 in different tumors. We searched an online website Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) to investigate the differential expression of C3 mRNA in glioma tissues and normal tissues. Then, we downloaded the clinical and transcriptional data of glioma patients from TCGA, CGGA, Rembrandt and Gravendeel database (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/). The immunohistochemistry data was downloaded in The Human Protein Atlas(https://www.proteinatlas.org/).

GO and KEGG Pathway Enrichment Analysis

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed on DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).Biological significance of differentially expressed genes was explored by GO enrichment analysis including biological process, cellular component and molecular function. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed to explore the critical pathways closely related to C3 up-regulated malignant progression of glioma. We used the “ggplot2” package and “pathview” package (version 1.24.0), which were based on R software to do the visualization of the GO and KEGG signal pathway.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0) and R software (version 4.0). Low and high C3 expression groups were established based on the median C3 mRNA expression value in datasets. The relationship between C3 expression and a series of categorical variables were analyzed by t-test or Fisher exact-tests. Moreover, we employed a multivariate Cox regression model to probe whether C3 expression was an independent prognostic indicator in glioma patients. Kaplan-Meier curves were utilized to evaluate the prognostic significance of C3. P-values less than 0.05 on both sides were statistically significant.

Result

Complement C3 Plays an Important Role in the Malignant Progression of Glioma

In the ONCOMINE database, the complement C3 is highly expressed in most tumors (Figure 1A). We use GEPIA to analyze the mean expression levels of complement C3 in tumor tissue and paired normal tissue, and find that complement C3 is high in glioma (Figure 1B). To explore the prognostic significance of complement C3 in glioma, we analyze the TCGA-GBMLGG database and found that C3 high expression can promote the malignant progression of glioma (P<0.001)(Figure 1C). The same conclusion is verified in CGGA, Rembrandt and Gravendeel database (Figure 1E-G). We use a multivariate COX regression model to analyze detailed associations between C3 expression and clinical features. As shown in (Table 1), the expression of complement C3 is an independent factor to affect patient survival.

Figure 1: Complement C3 plays an important role in the malignant progression of glioma

(A). The expression of C3 in 20 different types of cancer diseases. Numbers represent the number of high (red) and low (blue) expression databases.

(B). The C3 expression profile across all tumor samples (red) and paired normal tissues (black). The height of bar represents the C3 median expression of certain tumor type or normal tissue.

(C). Heatmap showing distribution of C3 expression and clinical features in TCGA GBMLGG database.

(D-G). Overall survival of GBM patients grouped by C3 median expression in TCGA GBMLGG, CGGA, Rembrandt and Gravendeel database.

Complement C3 Causes Malignant Progression of Glioma Through Nf-Kb and Jak-Stat Signaling Pathway

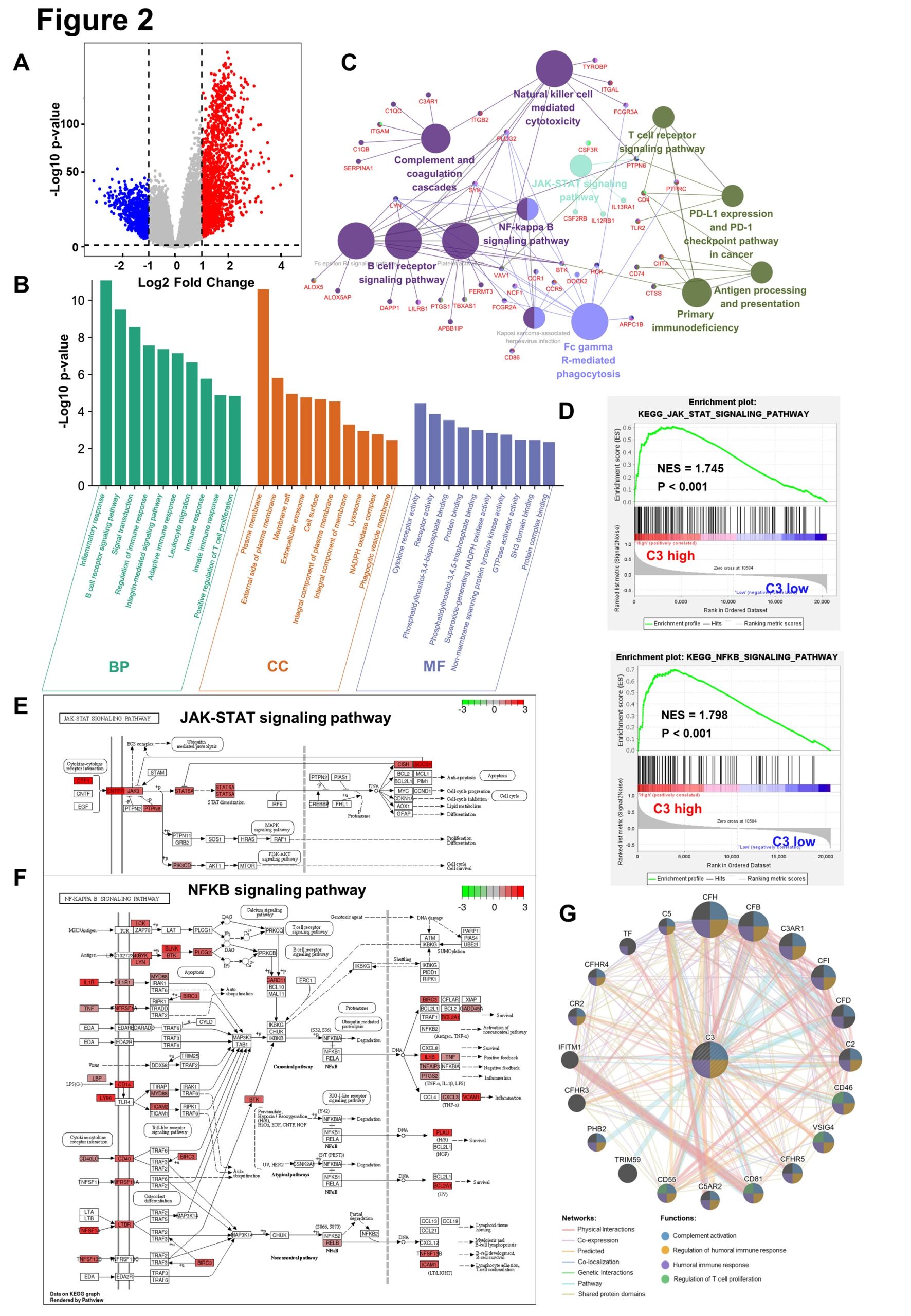

In the TCGA-GBMLGG database, C3 high group and low group do difference analysis, to obtain 1501-regulated genes and 731 down-regulated genes, based on the cut-off criteria (P<0.05 and fold change≥2) (Figure 2A) . The up-regulated genes in the top 200 p-values are selected for GO biological function enrichment analysis. In terms of biological process, C3 up-regulated genes are significantly enriched in the inflammatory reaction and immune response.For cellular components, C3 up-regulated genes are significantly enriched in cell membranes and extracellular matrices. Regarding the molecular function, the up-regulation genes are significantly enriched in cytokine receptor activation (Figure 2B). These significant enrichments can help us further understand the role of C3 in glioma occurrence and progress. Furthermore, KEGG pathway enrichment analysis shows that the C3 up-regulation genes are associated with NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways (Figure 2C). Similarly, GSEA also reflects that the C3 high expression group up-regulates NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways (Figure 2D). The KEGG analysis reveals that C3 up-regulated genes increase the expression of the relevant genes of these two signaling pathways, thereby promoting the malignant progression of gliomas (Figure 2E-F). Gene co-expression network is constructed to detect genes showing similar trends (Figure 2G).

Figure 2: Complement C3 causes malignant progression of glioma through NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathway.

(A). Volcano plot for showing C3 differential expression in TCGA GBMLGG database.(fold change >=2 and p < 0.05).Non-changed genes are shown in gray color. Red color is indicative of up-regulated genes and blue is indicative of down-regulated genes.

(B). Histogram for showing GO biological function enrichment analyses of C3 up-regulated genes. Biological process enrichment analysis (green), Cell component enrichment analysis(orange) and molecular function enrichment analysis(blue).

(C). Network diagram for displaying KEGG pathway enrichment analyses of C3 up-regulated genes. Large circles represent different signaling pathways, and small dots represent genes enriched in pathways. The lines represent the regulation relationship between genes and pathways.

(D). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) between group high C3 expression and C3 low expression shows NFKB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways.

(E)~(F). Gene expression in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and NFkB signaling pathway were plotted by PATHVIEW. Red represents up-regulated genes, while green represents down-regulated genes in C3 high expression group.

(G). Construction of gene co-expression networks. The lines represent co-expression networks and the dots represent functions.

Complement C3 Specifically Promotes the Growth of Mesenchymal Subtype Gliomas and Trigger Chemoradiotherapy Resistance

Immunohistochemical staining reveals that C3 is highly expressed in high-grade glioma, especially in area of necrosis (Figure 3A). In the Rembrandt database, C3 mRNA is highly expressed in MES subtype glioma (Figure 3B). C3 high expression and MES subtype correlation signaling pathways are significantly enriched (P<0.01) (Figure 3C). In fact, MES subtype gliomas are highly radiotherapy and chemotherapy resistant. Therefore, we analyze the effect of different treatments on the prognosis of glioma. We found that chemoradiotherapy can significantly prolong the survival of glioma patients (Figure 3D). However, in the group of chemoradiotherapy, C3 high expression might cause chemoradiotherapy resistance in glioma patients and affect their prognosis (Figure 3E).

Figure 3: Complement C3 specifically promotes the growth of mesenchymal subtype gliomas and trigger chemoradiotherapy resistance.

(A). The immunohistochemistry of complement C3 in normal tissues(n=3), low-grade gliomas(n=4), and high-grade gliomas(n=11). The data was downloaded from The Human Protein Atlas. The box plot showing the quantification of the C3 positive rate in different tissues. ‘ns’ represents no significance, *P<0.05.

(B). The box plot shows the C3 mRNA expression level of different glioma subtypes in Rembrandt database. (Non-tumor, n=28; PN, n=76; CL, n=72; MES, n=71). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001.

(C). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) between group high and low of C3 expression showed signaling pathways of different glioma subtypes in TCGA GBMLGG database.

(D). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the different treatment groups of the TCGA GBM database (Only Chemotherapy, n=10; Only Radiotherapy, n=53; Chemoradiotherapy, n=324). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

(E). Kaplan–Meier survival curves for the high(n=162) and low(n=162) mRNA expression level of C3 in chemoradiotherapy group(n=324).

Table 1: Multivariable Cox Regression Analysis in C3 expression levels and clinical features. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Discussion

Gliomas account for approximately 80% of primary central nervous system (CNS) malignant tumors, with high invasiveness, recurrence, high mortality and other characteristics [2]. Currently, the standard treatment for glioma is surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy [22,23]. In fact, due to the deep location of glioma and chemoradiotherapy resistance, the prognosis of patients remains poor [24,25]. Therefore, in response to these difficulties, we need to propose new treatment options.

Studies have shown that patients with MES signatures belong to the poor prognosis subtype and are resistant to standard treatments [26,27]. In this study, we analyzed that C3 high expression causes chemoradiotherapy resistance in MES subtype gliomas. We also found that C3 high expression promotes chemoradiotherapy resistance in gliomas through NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathways. Similarly, a previous study found that a subset of the PN GSCs undergoes differentiation to a MES state [28] in a TNF-a/ NF-kB-dependent manner with an associated enrichment of CD44 subpopulations and radioresistant phenotypes [29,30]. They further show that the MES signature, CD44 expression, and NF-kB activation correlate with lower radiation response and shorter survival in patients [30].

In summary, the expression of C3 is an important factor affecting the chemoradiotherapy resistance of gliomas. Our data shows that C3 high expression may activate NF-kB and JAK-STAT signaling pathway to promote the chemoradiotherapy resistance of glioma, leading to poor prognosis. Therefore, it is a new therapeutic scheme for targeting C3 and associated signaling pathways to inhibit the chemoradiotherapy resistance of gliomas and improve the prognosis of patients.

More information regarding this Article visit: OAJBGSR